Plants are ubiquitous. They can be found anywhere in any country and whatever piece of land no matter how extreme its conditions are. Without them, though, our planet as we know it would fail to exist. One simple example that enforces the importance of these chlorophillian creatures is the fact that a staggering number of animal species consume them. Some are familiar, like large grazing mammals including deer or cattle, while others, much narrower in size, are the hundreds of thousands of insect species and related arthropods.

And while a flowering plant fails to uphold a brain, this does not mean that it cannot defend itself and ensure the survival of its species in light of this aggressive phytophagy. This article is all about the defense mechanisms that evolved over the course of hundreds of thousands of years to assure the continuity of the flora and overcome the constant onslaught of animals.

Various Defense Mechanisms

Animals use many ways to avoid their predators. Behavioral responses, like running away, are very important. In contrast, plants are “sessile,” meaning that they cannot move. Roots anchor them to the soil, so plants can’t run away. Therefore, they’ve developed physical and chemical defenses to protect themselves against herbivores, which are animals that live by eating plant tissues.

Physical defenses are the first and most rudimentary line of protection for many plants. These defenses make it difficult for herbivores to consume them. Examples of physical defenses are thorns on roses and spikes on trees like hawthorn which hurt herbivores and stop them from eating plants’ stems or leaves.

Another form of defense is noticed with grasses, like maize (corn), rice, and wheat which take up the element silicon from the soil. Hard silicon particles make the grass leaves abrasive, wearing down the teeth of large grazing mammals and the mandibles of grasshoppers.

Another armament used by plants against insects can be detected in the leaves of some plants which feel fuzzy to the touch. This is a result of small structures called trichomes. A dense “forest” of these makes it harder for insects or mites to reach cells in the plant leaf.

Plants also use a diverse arsenal of chemicals that ward off herbivores. Many of these compounds are toxic, repelling or even killing to grazing herbivores. In other cases, the impact of these defenses is indirect. For example, some plants produce nectar that attracts ants. The ants feed on the nutritious nectar the plant makes. In return, the ants defend the plant from herbivorous insects that eat the plant’s leaves.

Plant defenses. From left to right: thorns on a rose, ants that kill herbivores feeding on plant nectar, tea leaves that contain caffeine (toxic to insects) and the microscopic silica serrated edge of a grass leaf.

Constitutive vs. induced plant defenses

Defense comes at a price. Plants need energy to create physical and chemical defenses, and a lot of times, they divert energy that could be used for growth to deploy their resistances. This explains why many plants only turn their defenses on when there are herbivores feeding on them.

In some areas, like tropical forests, large numbers of herbivores are present year-round as they munch on plants and shrubs. Any plant population would be eradicated at this rate if no action is taken. Therefore, toxic compounds are always present at high levels in some tropical plant species. Plant defenses that are always “on” are called “constitutive” defenses.

In contrast, freezing winters keep herbivore populations down in temperate regions while it expands during the remainder of the year. While plants still use constitutive defenses in these climates, when attacked by an herbivore, they can also increase the level of their defenses. These “induced” defenses save the plant’s resources until they are critically needed. For example, newly emerged leaves sometimes produce more trichomes. Many plants also ramp up production of certain compounds when they’re being eaten.

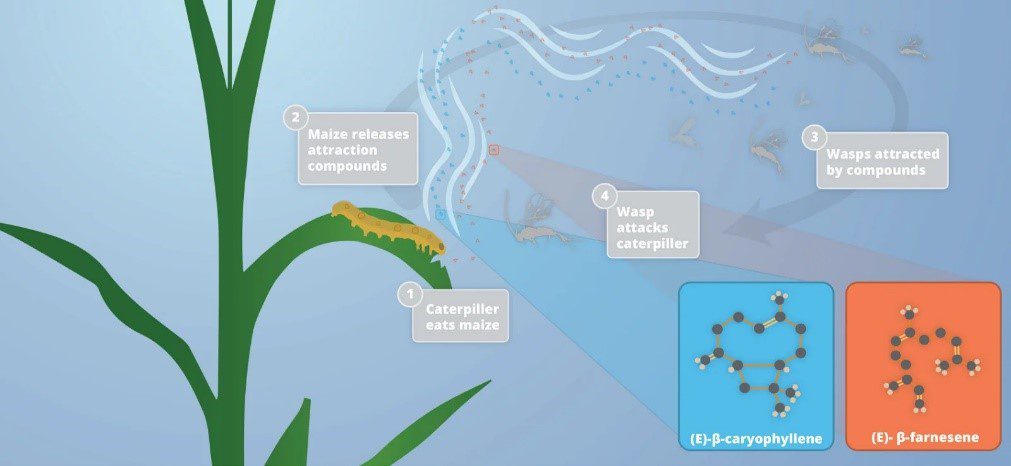

Maize has an “induced” defense that attracts the herbivore’s natural enemies. When herbivores start to eat maize, it triggers the production of air-borne compounds. These compounds attract wasps that attack herbivorous insects. When these predatory insects reach the plant, they find a victim waiting for them.

For plants in tropical regions, like this forest in Indonesia, toxins can make up as much as 50% of the leaf tissue.

Perception of herbivores

Plants recognize attacking herbivores within minutes to hours. In response, they can turn genes on and off, generating enzymes and other proteins to counter the attack. Herbivores physically damage plants when they eat their tissues or drink their fluids. Being wounded activates chemicals in the plant at feeding sites, and the herbivore’s saliva can sometimes trigger chemical responses in plants. In response to these signals, plants produce compounds like hydrogen peroxide that deters insects.

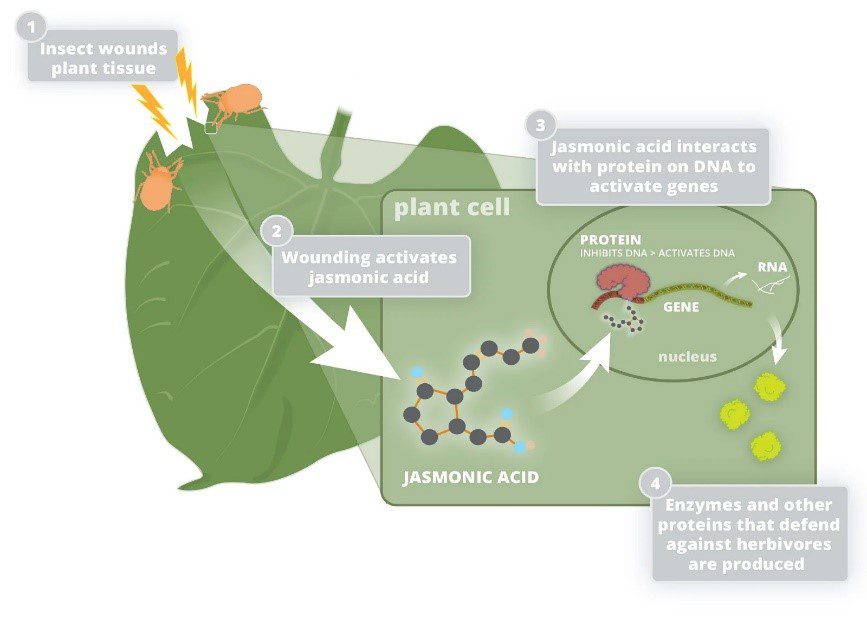

Another compound produced during the defense mode is jasmonic acid (JA). This chemical serves as a “master regulator” of induced plant defenses. Within 24 hours of an herbivore attack, many thousands of genes can be activated via the JA system. These genes encode proteins with diverse impacts on herbivores. Some damage their digestive systems, and others disrupt cell functions that are critical for herbivore growth, survival or reproduction.

When activated through wounding, jasmonic acid (JA) interacts with proteins on DNA in the plant cell nucleus. These proteins inhibit genes until they’re needed. When JA binds to the proteins, the genes are freed from inhibition. A diverse array of genes begin producing proteins and enzymes needed for plant defense.

Jasmonic acid (JA) is a plant hormone. Almost all plants have it. JA is responsible for controlling many plant responses, not just defense. For example, JA directs the formation of tubers in potato plants. It also orchestrates how tendrils coil on vines.